“THE POLITICS OF PROCESS” | U OF C

On Friday, January 27th 2017, The Fourchettes discussed the impact of ethnographic work on themselves, on the subjects of their research, and on the audiences for whom they write. This session was part of Connections: The CMF Speaker Series, a monthly speaker series hosted by the Department of Communication, Media and Film at the University of Calgary.

Workshop Summary #1 | Mylynn Felt | PhD Candidate (Department of Communication, Media and Film)

Research is never a passive process. Nevertheless, some methods demand more active investment on the part of the researcher than others. This is particularly the case with ethnography and with narrative methods. To conduct ethnography is to embed oneself completely in the process of what is under investigation. It is to come to know the subjects of research as the people and the practitioners they are. Such research produces rich results. It is worth noting, however, how deeply such work impacts ethnographers. To produce narrative work as an academic output is to plait aspects of the self with research results.

As part of Connections: The CMF Speaker Series, a monthly speaker series hosted by the Department of Communication, Media and Film at the University of Calgary, three current researchers of such methodologies discussed the impact of this work on themselves, on the subjects of their research, and on the audiences for whom they write. Each of the speakers’ exemplifies the critical methods research being conducted by The Fourchettes network, which co-sponsored this Connections speaker event.

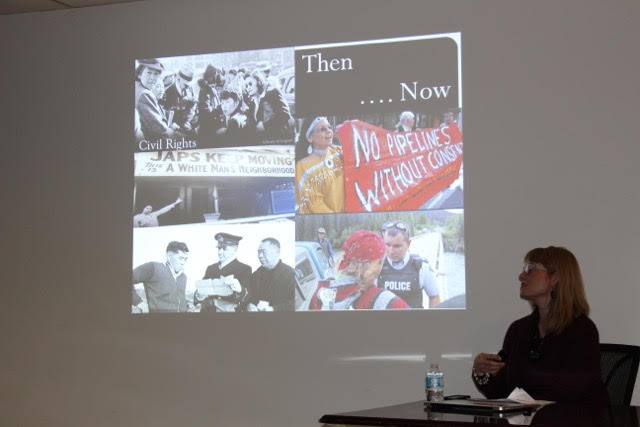

Sheena Wilson, Associate Professor with the Faculty Saint-Jean at the University of Alberta, spoke on the “Politics of Process: Processes of Protest, Feminist Energy Futures.” In examining feminist takes on petroculture and the oil industry, Wilson seeks the missing female voices in the male-oriented discourse of contemporary energy debates. After writing a short story about motherhood in petroculture, Wilson realized that she was reaching a new audience through her narrative work. This led her to create a short film titled “Petro-mama” and to begin work with women, encouraging and challenging them to write of their own experiences. She finds great power in the narrative form.

AnneMarie Dorland, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication, Media and Film at the University of Calgary, spoke on “Design Thinking + Design Doing: A Study of Creative Practice in Design Studios.” Dorland is conducting an ethnography in which she researches designers who are doing research and design in an international design studio of about 850 employees. She is finding that as designers conduct research similar to ethnography, they are uncomfortable with self-identifying as researchers or as ethnographers themselves. They think of their work as designing or as creating products for their clients even when they conduct what they phrase a participatory design work.

Mél Hogan, Assistant Professor with the Department of Communication, Media and Film at the University of Calgary, spoke on “The Politics of Process: Ethnographic Work with/in Data Centers: A Reflection on What It *Feels* Like to Do Research.” Hogan conducts research on data centres and recently returned from a trip to Sweden during which she conducted preliminary ethnographic research. While the engineers at this data centre were open to her research and willingly agreed to interviews, she found herself wanting to open more lines of communication. This led to a reflexive stance on her part and to efforts to create a Podcast in which she could share her research findings in a more open and inclusive way for the general public and for the subjects of her research.

This panel opened important questions about the position of the researcher and her relationship with her research subjects. Each revealed moments of vulnerability as an academic approaching a community not necessarily her own. They discussed some of the challenges of conducting embodied research in which they become personally invested. In discussing the politics and the process of such research experiences, they conveyed themselves as political and affective beings, sometimes feeling all the insecurities of junior high or relying on mundane topics such as hockey to find entry points in the relationship with research participants. The thick description of ethnography and the creative labor of narratives require time and personal investment. The speakers of this Connections panel conveyed the power of narrative and ethnography while acknowledging the personal challenges to those who choose to conduct this important work.

Workshop Summary #2 | Sheena Manabat | M.A. (Communication, Media and Film)

On Friday, January 27th, 2017 I attended the January edition of Connections: The CMF Speaker Series, “The Politics of Process”. As a graduate student in the Communications, Media and Film department, I found this panel valuable to me in tangible ways. The panel highlighted the participatory nature of research itself, how research always brings a degree of researcher reflexivity, and how the research should not discount the research subjects after the work is completed. The speakers discussed their respective academic projects, and how these allowed them to gain insight into the process of doing the research itself. All three raised crucial issues that researchers should take into account when doing research involving human subjects.

Dr. Sheena Wilson, Associate Professor in the Faculty Saint-Jean, joined us from the University of Alberta to discuss her research into discourses and representations of the oil sands from a feminist perspective. Her research piqued my interest because of its relevance to Alberta and her argument that patriarchal discourse has historically omitted feminist knowledge, traditionally preserved through stories or other creative means. Wilson spoke about how breaking out of the traditional academic sphere allowed her to reach other audiences and engage with different groups in new ways. She also acknowledged the ways in which doing research as a white woman affects interaction with different research subjects.

AnneMarie Dorland, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication, Media and Film, is currently examining how designers and industry use ethnographic research methods in their field. Dorland noted that, in some respects, she is engaging in a meta-analysis, since the cultural producers she studies are conducting research themselves. For Dorland, these “levels” of research require reflexivity on her part, as her subjects reject the imposition of the term “research” on their cultural work, preferring instead to be called “designers”. The lack of nuanced ethical and moral considerations of research outside of the labels “ethnography”, “participatory design” or even “research” allow a broad range of methodology for designers that may be perceived as questionable in the academic sphere. Dorland also acknowledged that designers might be doing work for a capitalist system and therefore there is an interesting relationship between data, power and capital. Still, she acknowledged her process was complex, reflecting the intricacy of conducting ethnographic studies within a design organization that has real world impacts.

Dr. Mél Hogan, Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication, Media and Film, provided a personal presentation on what it actually feels like to do research. Since 2011, Hogan has done research on data centers, which can be hard to access. Hogan’s last ethnographic trip to Lulea, a small town in Northern Sweden, allowed her to initiate a research relationship with contacts for when she returns for a subsequent research trip. She addressed the collaborative aspect of ethnographic research and the variable role of transparency in the collaboration between researcher and research subject (for instance, a researcher may not accurately anticipate the politics of their interview subjects). Hogan also made practical suggestions for those engaging in ethnographic study, such as writing “field notes” after engaging in a critical conversation. These notes, which may not initially seem significant, may prove quite valuable at a later point in the research process. Hogan also addresses creative methods of capturing and circulating research, such as podcasts. A podcast, she noted, provides opportunity for participants’ voices to be heard in the way that they intended, making a critical intervention in the research process. Hogan’s talk reminded me that all scholars who conduct this type of work experience the research process differently, and it is important to document and be aware of your own subjectivity.